At the height of the Jim Crow era, Joseph Ward blazed trails for black Americans.

Genealogists say the most important thing on a headstone is the dash between the date of birth and date of death, for that dash represents the life lived.

At the top of a gentle rise in Indianapolis’ 550-acre Crown Hill Cemetery is the final resting place of Lt. Col. Joseph H. Ward (1872-1956), an African American surgeon, hospital administrator and World War I veteran. Like most military markers, Ward’s offers few clues to his dash – his many accomplishments, in and out of uniform.

I first came across Ward’s name while doing research before returning to college, and came to appreciate his legacy while doing additional dissertation research. I learned that Ward established and operated a hospital for black patients when they were barred from treatment elsewhere. Digging further, I discovered he was a medical trailblazer and early American Legion member whose achievements – decades before the civil-rights movement – have been largely forgotten.

EARLY YEARS Ward was a first-generation freedman, born near Wilson, N.C., on the same plantation where his mother, Mittie, grew up enslaved. His maternal grandfather, David G. Ward, a physician, owned the plantation. However, his grandfather took no interest in young Joseph or his education.

As a teenager, Ward left North Carolina and lived in the Baltimore-Washington, D.C., area before settling in Indianapolis. There, he lived with and worked for Dr. George Hasty, one of the founders of the Physio-Medical College of Indiana and editor of the Physio-Medical Journal. Hasty saw to it that Ward completed his education – eighth grade, followed by three years at Indianapolis High School (later Shortridge High School, class of 1894) and the Physio-Medical College of Indiana in 1897. Ward did additional training at the Indiana Medical College in 1900. In 1902, he attended advanced training in modern surgical techniques at Polhemus Memorial Clinic in New York, which pioneered the use of inhalation anesthetics.

Ward wanted to be not only a doctor, but a surgeon – goals made practically impossible by 19th-century social norms and segregation policies of the Indianapolis City Hospital. In 1901, he opened a small office at 435½ Indiana Ave., where he was one of eight African American doctors in Indianapolis – a city with a black population of 169,000. Undaunted, he went on to open Ward’s Sanitarium, a privately owned hospital and surgery center located on the second floor of a large house at 722 Indiana Ave., offering medical services to anyone.

In 1908, Ward was elected president of the Aesculapian Medical Society, the Indianapolis chapter of the National Medical Association. He also served as vice president of the National Hospital Association, a group for black-owned hospitals (a counterpart to the American Hospital Association). By 1922, African Americans in Indiana needing surgery were coming from as far as 100 miles away.

THE WAR YEARS On April 6, 1917, at the request of President Wilson, Congress declared war against Germany. Not long after, the U.S. government called on African Americans to join the cause, on the heels of Wilson’s public praise of D.W. Griffith’s racist film “Birth of a Nation,” which had played to sellout crowds. Some 350,000 blacks served, 10,000 of whom never returned home; most are buried in U.S. military cemeteries in France.

Ward joined the Army, intending to serve as a doctor. He was already a respected surgeon, proprietor of a successful private hospital, with a wife and two children. At 45, and with no military experience, Ward was under no obligation to serve, yet in an interview with the Washington Bee he said that something important was happening in the world and he wanted to be a part of it.

At the Medical Officers Training Camp (Colored) at Fort Des Moines, Iowa (a one-time experiment the Army never repeated), Ward’s skills as a physician and administrator got the training staff’s attention, and he was recommended for promotion.

As one of the 104 black doctors and dentists who served in the Army during World War I, Ward was assigned to the 325th Signal Battalion, 92nd Infantry Division. On June 10, 1918, 1st Lt. Joseph H. Ward, M.D., along with members of a medical detachment of the 325th Field Signal Battalion and 3,000 men of the 92nd, departed for Europe at Hoboken, N.J., aboard USS Orizaba, a U.S.-flagged ocean liner requisitioned by the Army.

Being a medical officer in a combat zone can, at times, be as hazardous as serving as an infantryman, as Ward and other members of MOTC (Colored) learned with the death of 1st Lt. Urbane Bass of Virginia. Bass was among the group of black doctors and dentists commissioned at Camp Des Moines, and was assigned to the 372nd Infantry Regiment, 93rd Infantry Division.

On Oct. 6, 1918, Bass was treating wounded soldiers at a dressing station near Monthois, France, when a shell exploded near him, showering him with shrapnel and severing both legs. Bass died from shock and blood loss before he could be evacuated, and was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism. He was the first black commissioned officer to be buried in Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

By war’s end, Ward had been promoted to major and was in command of a U.S. Army field hospital in Europe. At the time, he was the first of two African Americans in Army history to achieve that level of authority and responsibility.

Ward returned to the United States aboard SS La France, arriving in New York City on Feb. 9, 1919. He went by train 60 miles east to Camp Upton, where he was held over to help care for returning veterans still recovering from illness and battlefield injuries.

While there, Ward received word that his most famous patient and America’s first female millionaire, Madam C.J. Walker, had fallen critically ill while visiting St. Louis. Ward and his wife were close friends with Walker; the couple helped launch the Walker Manufacturing Co. in 1911.

The Army granted Ward emergency leave, and he arrived in Irvington, N.Y., to meet Walker’s train and accompany her home. Just after 7 a.m. May 25, 1919, Ward came down from Walker’s bedroom and announced her passing. Following her funeral, Ward continued working at Camp Upton for a short time, then returned to Indianapolis in June 1919 after completing more than two years in uniform. He remained in the Army Reserve and cultivated connections made during his military service, seeds that would blossom into a government career.

In Indianapolis, Ward rebuilt his medical/surgical practice and adjusted to civilian life. He and his wife, Zella, also grappled with the loss of their son, 9-year-old Joseph Jr., who died during the 1918 flu pandemic.

NEW ASSIGNMENT In 1924, Ward was appointed chief medical officer and administrator of the segregated Veterans Hospital No. 91, a 600-bed facility built to accommodate black veterans of the Great War (later renamed Tuskegee VA Hospital). Larger than most U.S. hospitals and with an annual payroll of $1 million, it rivaled white institutions.

Ward’s appointment was not without controversy. The Harding and Coolidge administrations had resisted appointing any African American to the staff, let alone leadership. In 1929, the Journal of the National Medical Association published an article about the hospital and Ward’s performance, reporting that all was well there even among those who had initially opposed the hospital and its staffing. Unfortunately, the perceived tranquility after Ward’s appointment was a façade.

White residents of Macon County, Ala., and some government officials resented having an African American in such a high-profile position. A well-dressed Ward was often seen riding his horse around the expansive 450-acre hospital grounds, to Tuskegee University and throughout the town.

The situation was intolerable to local whites who opposed having the new veterans hospital staffed and led by African Americans. Given free rein, Ward recruited several physicians with whom he had trained and served in the Army. He appointed black dentists, a black head nurse and a black head dietitian, all of whom employed black subordinates. The dietitian purchased vegetables and meats from local black farmers first, paying them market rate and further irritating local whites. Soon senators and representatives suggested to Ward that he stop doing business with the black farmers, but he continued.

Coupled with a modern, well-operated hospital facility, Ward’s professionalism and leadership style were more than some could stand. Accusations began to swirl about poor management practices and wasting of government funds.

By 1936, some in the federal government had become annoyed with Ward, the staff and the entire concept of the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital, though it had passed all inspections and records checks without problems.

Writing for The Crisis, surgeon and civil-rights activist Dr. Louis T. Wright said, “I am told that this hospital has been rated since it was first established as one of the best-managed Veterans Hospitals in the country, both administration and in the character of scientific work done.”

Dr. Joseph Garland of Massachusetts General Hospital called Tuskegee Veterans Hospital “one of the best conducted. The two hospitals at Tuskegee probably comprise the most fertile field for clinical material that the Negro race possesses.” Patients were well cared for and registered no complaints.

Ward returned to Indianapolis in 1936 but was never able to return his sanitarium to its former level of prominence. Indianapolis had moved on; Ward’s Sanitarium was no longer the only viable option for the African American community. The Indianapolis City Hospital was beginning to desegregate and allow black doctors to practice medicine there. The costs of equipping a surgery facility had escalated, too.

Ward practiced medicine for another 15 years until his retirement. He died Dec. 12, 1956, at the West 10th Street Veterans Hospital (now Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center), following a stroke. He was buried next to his wife and son.

During his lifetime, this first-generation freedman became a successful physician, surgeon, entrepreneur, Army officer, hospital administrator, civic leader, and prominent member and commander of American Legion Post 107 in Indianapolis, all during the height of the Jim Crow era (1896-1954), between Plessy vs. Ferguson and Brown vs. Board of Education.

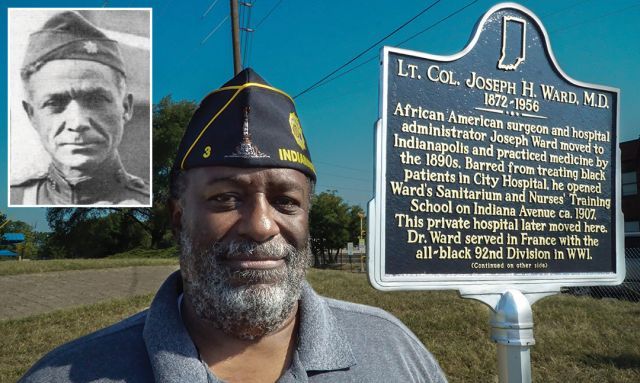

In August 2019, the state of Indiana dedicated a historical marker at the former site of Ward’s Sanitarium commemorating his achievements. The marker’s installation and dedication would not have been possible without the emotional, financial and physical support of Broad Ripple American Legion Post 3 and Tillman H. Harpole American Legion Post 249, and members of the 11th District of Indiana.

Leon E. Bates is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at Wayne State University in Detroit. He is an Army veteran and member of Broad Ripple American Legion Post 3 in Indianapolis.

- Magazine