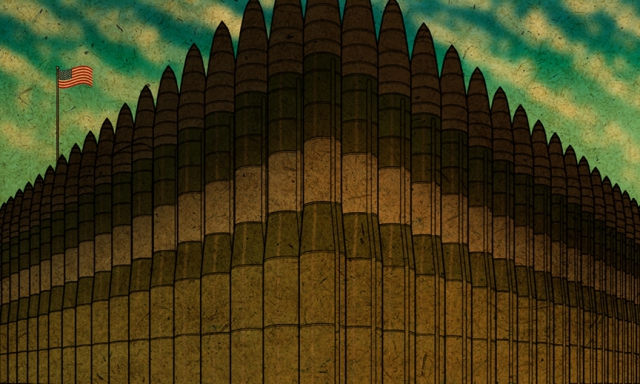

A world without nukes takes us backward, not forward.

Post-Cold War history has not been kind to the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

After outlasting the Soviet Union – the only peer state with the wherewithal to mount a challenge to American economic/military/industrial/nuclear pre-eminence – the United States has spent nearly a quarter-century waging a mix of conventional wars, police actions, counterinsurgencies, and nation-building and stability operations.

Some of these interventions involve death-wish dictators seemingly immune from deterrence; others involve non-state actors who don’t play by the rational rules that governed the Cold War at all. All of them highlight an asymmetry of power. In short, the nuclear deterrent – so central to the security of the United States and its allies in decades past – seems irrelevant to today’s threats, leaving too many Americans to question the value of the most powerful weapon in the arsenal.

For nuclear abolitionists, the decline in the visible threat posed by Moscow – and in the day-to-day relevance of the nuclear deterrent – is proof that nuclear weapons are a Cold War anachronism. Recent years have seen them ride a wave of political momentum: in 2007, Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, William Perry and Sam Nunn penned an eyebrow-raising essay calling for “a world free of nuclear weapons.” In 2008, the Global Zero movement was born, its organizers urging nuclear powers to eliminate all nuclear weapons by 2030. President Barack Obama vowed in 2009 “to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons” and signed the New START Treaty in 2010, whittling the U.S. strategic arsenal down to 1,550 warheads.

These well-intentioned opponents of nuclear deterrent believe they are pointing the way to a better and safer future. “So long as nuclear weapons exist,” Obama argues, “we are not truly safe.”

But what if the opposite is true? What if the U.S. nuclear arsenal is the very thing that has kept us safe? What if the path to a world without nukes carries us not forward to a safer tomorrow, but backward to the ghastly great-power conflicts of yesterday?

INSURANCEPerhaps the least appreciated but most important fact about the U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal is that Washington has, contrary to popular belief, used nuclear weapons to defend our sovereignty every single day since Aug. 6, 1945. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear weapons took over the central role in deterring America’s adversaries from attacking the homeland. To be sure, nuclear weapons have not prevented every adversary from challenging the United States, but nuclear deterrence can be credited with ensuring that the Cold War never turned into a third world war.

It’s no coincidence that between 1914 and 1945, before the advent of the bomb, some 76 million people – including no less than 522,000 U.S. military personnel – were killed in two global wars, or that there have been no global wars in the 70 years since. In other words, nuclear weapons have paradoxically kept the peace between great powers and between nuclear powers. Along the way, they have promoted stability, enhanced U.S. security and bolstered American primacy.

If our understanding of American, Russian, Chinese, British, French, Indian and Pakistani nuclear thinking – a decidedly diverse group of nuclear-weapons states – shows us anything, it is the continued relevance of nuclear weapons in giving adversaries pause when contemplating acts of aggression. It is for good reason that none of these countries have gone to all-out war with one another since developing nuclear weapons, despite deep-seated animosities.

Even so, it’s increasingly common to hear that America’s nuclear triad – intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), nuclear-capable bombers and ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) – is no longer required to deter nuclear-weapons states. Critics of the triad argue that maintaining three nuclear-delivery platforms is expensive overkill.

The problem with this argument is that it fails to appreciate the unique attributes of the triad. With their distinctly different strengths and weaknesses, ICBMs, bombers and SSBNs combine to create a nuclear force that provides stability, flexibility, visibility, survivability, responsiveness and global reach.

Let’s start with the bedrock of U.S. strategic stability: ICBMs. If the United States decommissioned its ICBMs tomorrow, adversary nuclear targeting would decline from 504 possible targets to six. Such a reduction in targets would be provocative and would increase the probability that an adversary would be tempted to launch a decapitating pre-emptive strike aimed at eliminating the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Relatedly, ICBMs dramatically increase the risk an adversary must be willing to accept in order to attack the United States. Unlike bombers that can be shot down, or submarines that can be sunk, ICBMs require an adversary to launch a nuclear strike against 498 distinct, remote and hardened targets.

The fleet of B-52H and B-2 stealth bombers also faces considerable criticism from nuclear abolitionists, who suggest that these warplanes are not only provocative but unneeded because of nuclear submarines. What the abolitionists overlook is that these bombers perform both nuclear-deterrence and conventional-strike operations. When it comes to the attributes of the triad, they provide flexibility because a bomber can be recalled after launch, and visibility because the bomber force is the only leg of the triad that can be used to signal U.S. seriousness during times of tension. Absent the strategic bomber’s unique ability to signal Russia, China, North Korea, Iran or some future adversary of U.S. readiness to use nuclear weapons, it would be much more difficult to persuade such an adversary to back down.

Many critics of the nuclear arsenal view the ballistic-missile submarine as the only leg of the triad required for maintaining credible nuclear deterrence. Correctly, they point out that the SSBN is currently the most survivable leg. However, what they fail to appreciate is that space-based and subsurface tracking and detection systems are advancing in their technological development. Should the ICBM and bomber legs of the triad be eliminated, adversaries could focus their efforts on exploiting these technologies, as well as air and seaborne platforms, to track and target U.S. SSBNs. In addition, it pays to recall that it’s possible to sink a ballistic-missile submarine with a conventional torpedo, making it difficult to justify the use of nuclear weapons in response: imagine the dilemma a president would face if, after the triad were replaced by a submarine-only nuclear force, an adversary eliminated the entire U.S. nuclear deterrent with a handful of torpedoes.

What may be even more startling to many Americans is just how badly the U.S. nuclear enterprise needs modernizing. A 2014 Pentagon review found the nuclear force “understaffed, under-resourced, and reliant on an aging and fragile supporting infrastructure.” The B-52H was designed in the 1950s, rolled off the assembly line by 1961, and has radar systems from the 1960s. The B-2 was developed in the 1980s and recently celebrated its 25th anniversary. The B-61 gravity bomb, which can be dropped by the B-52H and the B-2, was manufactured in 1961. The nation’s ICBMs date from the 1970s, while the infrastructure supporting their deployment and maintenance dates from the 1960s. The current SSBN fleet entered service beginning in 1978.

Many nuclear-zero advocates cite the cost of maintaining the nuclear deterrent to bolster their case against it. Here’s what the numbers say: the departments of Defense and Energy spend approximately $31.5 billion on nuclear-weapons programs annually. By way of comparison, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimates that the federal government expends $65 billion on fraudulent, wasteful or improper payments each year – more than twice the cost of the arsenal. In fact, the total cost of the nuclear arsenal is less than 5 percent of the Pentagon’s budget. So when critics suggest that maintaining and modernizing the nuclear arsenal is unaffordable, they are simply incorrect. For less than 0.1 percent of the federal budget, the United States buys an enormous insurance policy – a level of security that few nations possess.

However, the U.S. deterrent isn’t solely about protecting the homeland. It is equally important that the United States credibly assure its allies that it has the capability and will to employ nuclear weapons in defense of any nation under America’s nuclear umbrella. With Russian aggression on the rise and Chinese claims to the South and East China Seas leading to small skirmishes and near-misses with U.S. treaty allies, efforts to further reduce the U.S. nuclear arsenal could lead one or more longtime allies to pursue an independent nuclear-weapons program. This is not mere conjecture. Allied military officials in Europe privately warn that if the U.S. arsenal dips below a certain threshold of operationally deployed strategic nuclear weapons, their governments would pursue independent nuclear weapons programs. Similarly, key lawmakers in Japan and South Korea have proposed fully independent nuclear forces.

As NATO declared in 2014, “The strategic nuclear forces of the alliance, particularly those of the United States, are the supreme guarantee of the security of the allies.”

Indeed, America’s out-of-sight, out-of-mind nuclear arsenal deters nuclear as well as conventional threats. Recall that when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev warned President Dwight Eisenhower about the Red Army’s overwhelming conventional edge in and around Germany, the steely U.S. commander in chief fired back, “If you attack us in Germany, there will be nothing conventional about our response.”

VALUES AND INTERESTSTo be sure, the president and other nuclear-zero advocates are in good company when it comes to their dreams of a nuclear-free world.

Winston Churchill said his preference to a balance of terror was “bona fide disarmament all round.”

Noting that the world “lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles,” President John F. Kennedy counseled that these weapons “must be abolished before they abolish us.”

President Ronald Reagan longed “to see the day when nuclear weapons will be banished from the face of the earth.”

But Obama is different in that he is not talking about a nuclear-free world in some far-off, theoretical future. As The New York Times noted, “No previous American president has set out a step-by-step agenda for the eventual elimination of nuclear arms.”

That agenda is ambitious. In the years since New START was signed, the Obama administration has floated proposals to cut the U.S. deterrent arsenal to 1,000 deployed strategic warheads, and even as low as 300.

The last time the U.S. strategic deterrent arsenal numbered 1,000 nuclear warheads was 1953 and 1954; the last time it was in the 300 range was 1950, when Moscow had five atomic devices.

A U.S. strategic arsenal of 1,000 warheads may be enough to deter a resurgent Russia, but is it enough to deter Russia, plus the growing number of other strategic threats?

- China’s military spending has mushroomed by 170 percent since 2004. The Pentagon reports that Beijing is modernizing its silo-based ICBMs and mobile-delivery systems. Once thought to be a last-resort deterrent of 100 warheads, China’s opaque nuclear force is now assessed by some outside experts to number 600 or more warheads. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission concludes, “China’s nuclear force will rapidly expand and modernize over the next five years ... potentially weakening U.S. extended deterrence.”

- Pakistan deploys about 100 nuclear weapons. Militants have attacked facilities linked to command-and-control and/or storage of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons at least four times since 2007, which explains why the United States has war-gamed neutralizing or securing Pakistan’s nukes.

- North Korea warned in 2013 that it was prepared to launch “a pre-emptive nuclear attack” against the United States and South Korea. In 2015, Beijing estimated that Pyongyang possesses 20 nuclear warheads.

- North Korea’s nuclear breakout serves as a cautionary tale. Iran wants to crash the nuclear club. A nuclear Iran would trigger Saudi Arabia and other Sunni states to go nuclear, touching off a nuclear arms race with widespread ramifications.

- We cannot view today’s Russia in the same light we viewed the Russia that signed New START in 2010. On the strength of a 108 percent military-spending binge since 2004, Vladimir Putin plans to deploy 400 new ICBMs. He is sending long-range bombers toward Alaskan airspace on simulated nuclear strikes, has violated the INF Treaty and withdrawn from the Nunn-Lugar nuclear-reduction program, conducts provocative war games on NATO’s borders (complete with mock nuclear strikes), and has invaded two sovereign neighbors.

Doubtless, many nuclear-zero advocates would cite these items to advocate a worldwide nuclear-disarmament treaty. However, treaties are only as good as the character of the parties that sign them. And America’s nuclear arsenal has a far better record securing and protecting U.S. interests than do treaties with regimes that don’t share our values or interests.

PRUDENCE If there is a silver lining in the storm clouds gathering, it may be that the nuclear-zero wave has crashed hard into reality – Russian aggression, Chinese bullying, North Korean nuclear tests, determined Iranian efforts to go nuclear – thus calling into question the prudence of further cuts to the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

That brings us back to Churchill, Kennedy and Reagan. Each hoped for a day when these dreadful weapons could be beaten into plowshares. But after decades of dealing with dictators, Churchill concluded, “sentiment must not cloud our vision.” So he called on freedom-loving nations to pursue “defense through deterrents,” noting that “but for American nuclear superiority, Europe would already have been reduced to satellite status.”

Kennedy was a realist. To deter Moscow, the U.S. nuclear arsenal grew 21 percent during his foreshortened presidency.

Because he believed, as Churchill once said of the Soviets, “there is nothing they admire so much as strength,” Reagan built up with the hope of one day building down. And because he knew “the genie is already out of the bottle,” he wanted an insurance policy against nuclear-missile attack. “What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that ... we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?” he asked. “This could pave the way for arms-control measures to eliminate the weapons themselves.”

Note the sequence: robust missile defenses would be in place before nuclear disarmament. Today, it seems Washington is trying to do the opposite.

To be sure, the world has changed since Reagan offered his roadmap to a day without nukes. But the value of the nuclear deterrent has not.

The story is told that Khrushchev, during a round of war games, could not bring himself to push the nuclear-launch button. Even pretending to fire a nuclear salvo was unthinkable to the man in charge of the Soviet nuclear arsenal. U.S. presidents have shared such an aversion to the use of nuclear weapons, which is exactly why they remain so critical in a world where the United States faces increased threats.

After 70 years of service, no other weapon has done more to protect U.S. sovereignty and deter America’s adversaries.

Alan W. Dowd is a senior fellow with the Sagamore Institute Center for America’s Purpose. Adam Lowther is a research professor at the Air Force Research Institute.

- Magazine