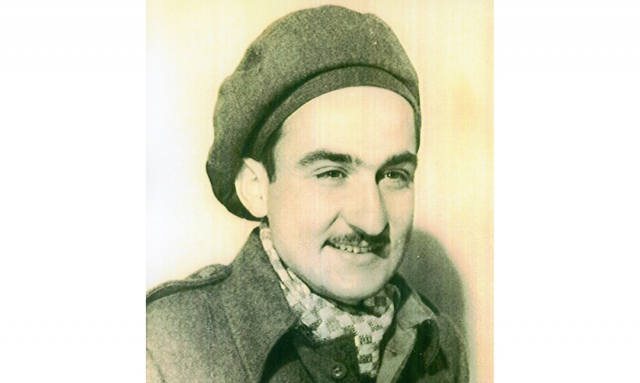

After 72 years, a distinctive POW photo re-emerges.

Bob Teichgraeber was held as a prisoner of war for 421 days at various German prisons during World War II. Like many veterans of his era, Teichgraeber rarely spoke about his war experience.

Unlike his World War II comrades, however, Teichgraeber stashed an unusual photo in a drawer in his Collinsville, Ill., home for 72 years. “I thought there was a stigma about being a captive,” said Teichgraeber, 97, a longtime member of American Legion Post 365. “That’s the way it was. I wasn’t vocal about it.”

The photo depicts Teichgraeber in a British Army uniform after he was no longer a POW. While it was common for the British to provide whatever clothes were available to freed GIs, World War II historians say such photos are rare.

Teichgraeber was captured Feb. 24, 1944, when his plane was among those hit upon returning from a bombing run over Gotha, Germany. “They shot down 12 of our planes before we reached the target,” he recalled. “One of our planes blew up in front of us; debris floated by. I saw two others with one of their twin vertical stabilizers shot off, go over on their side and then down.”

He fractured his right ankle when he parachuted out, landing in a farmer’s yard in Epstein, Germany.

Teichgraeber was among six crew members who were captured by the Germans and taken in a crowded boxcar to Frankfurt. Later in Stalag Luft 6, he was issued a cup, bowl and spoon, and a bunk bed with five slats and a gunny sack filled with straw for a mattress — “I could always remember that gunny sack.”

It would be the beginning of a long captivity, far from his base in England. “There was a vast difference from the warm Quonset hut, living on poker winnings, with better than average mess hall food, the frequent jaunts to London — always fish and chips — and the good times,” he said. “Without the workload, England was a great place for the GIs. But not this place!”

He recalls having access to war updates from the BBC, including news about D-Day. Still, the deplorable conditions, long marches and frequent moves strained the captives. “Guys would crack up and we wouldn’t know what to do,” he said of his time in the prisons. “It was horrible. The antics they went through. There was no quick fix to it. It was a pathetic deal.”

As the Russians drew closer, the Germans moved the prisoners.

“In July, we could hear Russian artillery,” said Teichgraeber. “The Germans evacuated the prison and put us in boxcars to the Baltic, then in a back hold of a coal ship, SS Mausuren. I was separated from my buddies in the dark boat and debarked in Poland. Then in boxcars to Stalag Luft 4. When out of the boxcars, they handcuffed two POWs together. They affixed bayonets on their rifles, had police dogs and double-timed us 3 kilometers to prison.”

From Feb. 6-8, 1945, the Germans evacuated Stalag Luft 4 Lager C. Teichgraeber and the 2,500 other POWs were forced to march in what would be called the 86-day hunger march.

“The first night was freezing,” said Teichgraeber, who still has one of his few possessions as a POW, a two-sided prayer card with a drawing of Jesus on the front. “We slept in a field on frozen ground — that’s when I met my buddy, John Bulla.

“Men were dropping out every day. I think John and I had two things going for us, we were young and the good Lord was keeping an eye on us. I think it was always the uncertainty of everything that bothered us.

During the march, the captives slept in fields, barns, or wherever the Germans decided. “All we saw was horses and wagons and once in a while an old truck,” he said. “Those people were behind the times by 50 years but they had the best armament in the world. They had years to prepare for the war. They had better weapons than we did.”

Sometimes they walked in strong snowstorms. “Sometimes, the only thing you could see was the guy ahead of you,” Teichgraeber said. “It was almost unbearable. Every day — almost every day — they would get us up and walk us.”

During captivity, the 5-foot-5 Teichgraeber went from 140 to 90 pounds. The brutal 86-day hunger walk was in the cold and snow, in addition to lice, fleas, dysentery and more. “We were young,” he says simply. “We endured it.”

Teichgraeber escaped April 19, 1945. He recalls staying in an abandoned home surrounded by farmland. One morning Teichgraeber and Bulla were awakened suddenly. “About 5 o’clock in the morning, the door opened up — ‘You’re free!’” Teichgraeber recalls one British soldier yelling. “We went out and found some rifles and bayonets.”

Teichgraeber and Bulla shared some eggs and a single potato. As they relished their first hours of freedom, the war remained close by — at one point a German shell landed less than 100 meters away. They took refuge in an abandoned home.

“We went into the basement of an empty house on account of those shells going off,” Teichgraeber recalled. “They had wine bottles on a rack down there. We got a hold of that wine and must have slept pretty good that night.”

The next day, we got to the British unit in a small town and went through their chow line. Then we went back and raided their garbage cans. “They came back and said we didn’t have to do that anymore,” he recalled. “They were stuck with us – couldn’t send us back to the Americans the way we were. We hadn’t had our clothes off for two months.”

The Brits cleaned them up, giving them a shave, haircut and British uniform for clothing. Then they were flown to Belgium to reunite with American troops.

Eventually Teichgraeber returned home to Illinois, where he took a job with National Cash Register and worked there for nearly 40 years. “One of the women I worked with said I looked like a scarecrow when I got home,” he remembered. “Well, that’s not very flattering.”

But, like many World War II veterans, Teichgraeber was reticent to talk about his service. They returned home to start families and careers

“I thought there was a stigma about being a captive,” he said. “That’s about the way it was. I wasn’t vocal about it. It was a stigma. The people I worked with didn’t know about it.”

More recently, after reuniting with the photo, Teichgraeber’s time as a POW has dominated his thoughts.

“Every day I think about it,” he says, motioning to a table overflowing with documents, maps and more about his experience. “It’s prevalent now because of this stuff here. You can remember so much vividly, but yet you can’t remember a lot.”

- Magazine