In Minnesota, the promise of a test for Gulf War Illness

Brian Engdahl sees the day when a blood test could remove all doubt about who’s suffering from Gulf War Illness. It may be less than five years away.

The key is the way an individual’s immune system is genetically programmed to respond to environmental insults, says Engdahl, a researcher at the University of Minnesota Brain Sciences Center and the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. Such insults include the toxic exposures veterans experienced during the first Gulf War.

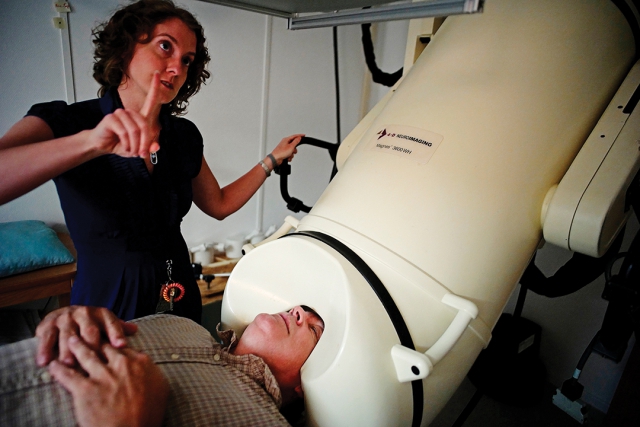

Engdahl and fellow researchers recently analyzed the health history, immune system genetics and brain scans of approximately 240 Gulf War veterans. Forty-six had no medical complaints. Ninety-one had medical problems, and another 98 had both medical and mental health issues. That variation indicates that some people are able to tolerate high levels of exposure to environmental toxins, while others become seriously ill. The difference appears to be determined by an individual’s particular human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex. Each individual’s HLA is determined by genetics. And the HLA type can be identified with a blood test.

This sort of diagnostic test is important because the symptoms Gulf War veterans exhibit may not fit established diagnostic categories. “Some veterans come in with some symptoms of chronic fatigue, but not all,” Engdahl says. This may result in the veteran being turned away for lack of a clear diagnosis. With the right blood test, “we will be able to say some very clear things about what is wrong with a veteran and how to treat it.”

The American Legion Department of Minnesota raised $1 million to endow the Brain Sciences Chair at the University of Minnesota and the Minnesota VA Medical Center in 1991, where Engdahl’s research is being done. Researchers at the center now want to try to replicate their results by studying 1,000 Gulf War veterans over the next three years.

“We could picture the day when a blood test would point the way to a treatment plan and give doctors a solid way to proceed,” Engdahl says. “It’s all part of a larger trend toward personalized medicine based on genetics.”

- Magazine