Veterans are baffled – and furious – as VA prepares to abandon a medical center that serves three states.

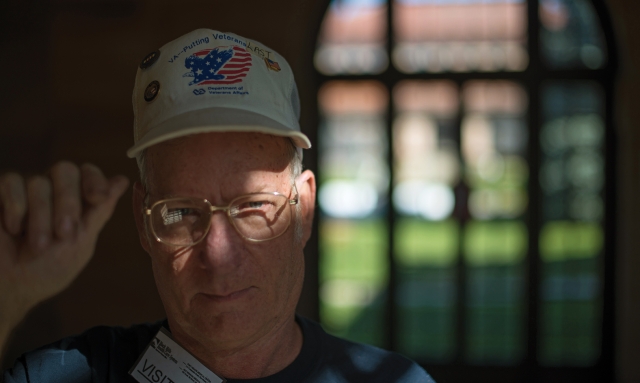

John Renstrom used to get all his medical care at a VA hospital near his home in the southern Black Hills of South Dakota. Now he drives 120 miles round-trip for everything from PTSD treatment to a 15-minute medication checkup. And soon, he and thousands of other veterans will have to travel even farther for medical care if VA closes the Hot Springs, S.D., medical center that has served three states and two of the nation’s most impoverished Indian reservations for more than a century.

“Hot Springs VA was the best preventive care a man could receive,” says Renstrom, a Vietnam War veteran. “Now they are going to take that away from me.”

“What are we going to do with young men coming home from the wars now?” adds Richard Galeano, another Vietnam veteran and a former Hot Springs VA employee.

Cutting services in Hot Springs runs contrary to efforts to expand veterans’ care in response to the scandals at VA hospitals in Phoenix and other cities where former servicemembers wait months to have urgent medical needs addressed. “The veterans we serve will be put into longer waiting lines at the VA medical center where they will be referred,” says Patrick Russell, an Army veteran and medical technologist at the Hot Springs VA.

There are also concerns that VA manipulated patient data, overstated maintenance costs and mismanaged medical staff to make closure of the Hot Springs medical center inevitable, Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., said in a letter submitted to the U.S. House Veterans’ Affairs Committee during an August hearing in Hot Springs.

Given these discrepancies and the resignations of the two most prominent supporters of closing Hot Springs – VA Secretary Eric Shinseki and Health Undersecretary Robert Petzel – VA should drop its Hot Springs “reconfiguration” plan, Thune added. “I believe VA should rescind its proposal and focus all of its energies on addressing the recent scandals and the pressing issue of veteran wait times.”

Extraordinary care Hot Springs VA is the town’s largest employer and an important source of jobs for veterans. It started as a sanitarium in 1907. A hospital was added in 1926, and the sanitarium eventually became a domiciliary renowned for PTSD and substance-abuse treatment. Some 87 percent of Hot Springs domiciliary patients remain clean and sober after completing the program here. Hot Springs is also widely praised by veterans for its medical care.

The campus included a 250-bed hospital when Renstrom started working there in 1989. It was one-stop shopping for veterans from western South Dakota, northern Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, and the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations.

“Veterans could see their doctors, get their X-rays and get their prescriptions filled,” he says. “Everybody went the extra mile to make sure people didn’t have to come back.”

Hot Springs VA has a reputation for being especially welcoming to Native American veterans and became home to the first sweat lodge built at a VA hospital.

“It is one place I can come and feel like I’m treated the same as my non-Indian counterparts,” says Bryan Brewer, president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, headquartered on nearby Pine Ridge.

Reversal of fortune Hot Springs’ fortunes changed in 1995 when Petzel became director of the VA region that includes western South Dakota. The Fort Meade VA hospital in Sturgis and the Hot Springs medical center merged into a single administrative unit called the Black Hills Health Care System. VA cut maintenance funds for the Hot Springs campus and transferred several medical services to Fort Meade. Hot Springs lost its intensive care unit, emergency room, all surgeries, cardiac rehabilitation and preventive services such as colonoscopies. The sleep lab and pacemaker clinics are gone. The hospital no longer even has the ability to ventilate patients with acute breathing problems, Russell says.

As consequences of these cutbacks accumulated, Petzel was promoted to VA undersecretary for health in 2010, but resigned last May after a litany of patient-care scandals came to light.

Meanwhile, VA has been slow to fill Hot Springs job vacancies and forced some medical staff to practice at both Fort Meade and Hot Springs, effectively adding a 200-mile round-trip commute to their job descriptions, says Ed Thompson, District 2 commander for the South Dakota American Legion. Moreover, VA has passed over qualified job candidates in favor of medical staff deemed less likely to stay in Hot Springs, according to Thune.

It’s been excruciating for veterans and Hot Springs VA staff alike. “This systematic dismantling has caused undue hardship on the veterans and lowered the morale of employees who have been bearing the brunt of a greater workload,” says Russell, who is also president of American Federation of Government Employees Local 1539.

Veterans and hospital employees started questioning whether VA secretly planned to close Hot Springs more than three years ago. After months of stonewalling, VA announced in December 2011 that it planned to “realign” the mission of the Hot Springs medical center and domiciliary – widely believed to be a euphemism for closing the campus. When asked to defend the proposal, “VA was unable to produce a cost-benefit analysis to justify the reconfiguration, leaving doubt as to how VA decided on its plan and raising suspicion that the change was directed by a political agenda,” Thune said.

The region was devastated.

“Some veterans cried when they announced the closure,” says author Mary Ellen Goulet, who compiled a book of essays by area veterans called “Reveille in Hot Springs” that makes the case for keeping the medical center.

Cloudy future Can the Hot Springs VA – and the town it supports – be saved?

Closing the medical center runs counter to the 2004 Capital Asset Realignment for Enhanced Services (CARES) Commission recommendation that VA continue to operate a hospital, domiciliary and outpatient services here. It is also mystifying given that South Dakota is constructing a $41 million, 100-bed state veterans home in Hot Springs that relies on the local VA hospital to care for its residents. In fact, VA contributed $25.4 million to the project, which replaces a veterans home that dates to the 1880s.

But VA says the Hot Springs medical center loses money and that the domiciliary requires expensive renovations to make it compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Maintenance costs on the old buildings are high, and it’s difficult to recruit medical staff to a small town in rural South Dakota. Veterans believe the latter problem is a consequence of VA failing to fill vacancies. “I’ve had nine different primary care doctors since 2009 and all of them said they would have stayed if they were offered permanent jobs,” Renstrom says.

Steven DiStasio, director of the Fort Meade and Hot Springs hospitals, is clear about his preferences: he wants to move. “I need a new building,” DiStasio says. “I would like to have it in Rapid City.”

DiStasio acknowledges that such a move will devastate the Hot Springs economy. Some of that could be offset if a private company repurposed the property, he says. When pressed to offer an example, he suggests that the Hot Springs VA is well suited to become a rental storage facility. “This building is never going to blow down, fall down, never going to get flooded,” he says of the regal sandstone block building that is on the National Historic Register.

“What are they going to store in that? Fly ash from North Dakota?” Renstrom replies.

More to the point, who will be left to store anything in a former medical center if VA pulls out of Hot Springs, population 3,800, and takes 370 federal jobs with it?

Math problems VA also argues that a declining number of patients will use the Hot Springs medical center over the next 20 years. But the agency’s own projections show almost no change in the veteran population in the Hot Springs service area. The evidence suggests that VA is driving patients away by cutting staff and eliminating medical services, Thune says.

VA is also excluding veterans from the nearby reservations when it calculates future demand for Hot Springs’ services, says Thompson, a member of the Oglala tribe. There are nearly 3,600 veterans at Pine Ridge alone, many of whom may not be aware they are eligible for VA care, and another 2,000 at the Cheyenne River and Rosebud reservations. VA dismisses those numbers, saying they can’t be verified.

The agency eventually produced a cost-benefit analysis of Hot Springs that has also been questioned. VA says it would have to spend $1.5 million to acquire land if it were to build a new domiciliary here, despite the fact that it owns ample acreage in Hot Springs, Thune says. VA also estimates it will have to spend $1.9 million to repair a maintenance building that essentially serves as a garage. And the agency lists $112,000 in expenses for a laundry building even though the agency closed the Hot Springs laundry services years ago, Thune says.

The agency’s budget also calls for spending $10 million a year to lease domiciliary space in Rapid City – an expense easily avoided if the facility stays in Hot Springs, says Navy veteran Bob Nelson Sr., who worked at the Hot Springs VA for nearly four decades.

VA did not respond to questions about these discrepancies.

Contracted care VA portrays the closure of Hot Springs as an opportunity for veterans to receive care close to home even though the closest VA hospital will be Fort Meade, another 100 miles north. Instead of forcing veterans to drive even farther for care, VA will pay for veterans to see private providers or, in the case of tribal members, the Indian Health Service, DiStasio says.

VA has little to back up that plan. More than two years after it announced its plan to close Hot Springs, Fall River Health Services – the only other hospital in town – told The American Legion’s System Worth Saving Task Force that it never received a formal proposal from VA. DiStasio confirmed that during a national commander’s visit to Hot Springs in May, saying it was premature to negotiate specifics.

A future deal between VA and Fall River may not do much to alleviate waiting times for veterans. Renstrom attempted to line up a private physician after learning he had heart problems. He was told it would take a minimum of 60 days for him to get an initial appointment, and 90 days before he could see a cardiologist.

“What the hell good does it do to tell me to go see a private-sector doctor when there aren’t any around here?” he asks.

Native American veterans adamantly oppose VA’s proposal to contract with the Indian Health Service for their care, Thompson and other tribal representatives say. Tribal veterans don’t always trust Indian Health Service hospitals, which are poorly funded, often understaffed and poorly supplied with sufficient medications.

There are also concerns about VA’s track record for reimbursing non-agency hospitals and clinics for contract care. That includes “long-standing compensation issues between VA and Indian Health Service,” Thune noted.

In fact, VA’s fee-for-service proposal could jeopardize health care throughout the region. Because VA reimbursement rates are so low, “rural hospitals run the risk of losing money on every veteran they treat,” Nelson says. “Add to that the slowness of the VA to pay their bills, and these hospitals are placed at greater financial risk.”

Veterans here also prefer VA care. “These local hospitals don’t know what the veterans’ issues are,” says Virgil Hagel of Gordon, Neb., a Korean War veteran and past department commander for the Nebraska American Legion who uses the Hot Springs VA. “Veterans were promised health care. We shouldn’t have to be up there fighting for it.”

Save the VA A citizens group called Save the VA formed soon after VA announced its plans to close the Hot Springs facilities, and drafted several proposals for keeping the campus viable. They include creating a national PTSD treatment center and a work-therapy program that would operate in conjunction with private businesses. VA abruptly stopped negotiating with the group in September 2012 and moved forward with plans to close Hot Springs.

The Legion’s System Worth Saving Task Force has recommended that VA upgrade the Hot Springs medical center and keep as much care there as possible, especially considering the needs of residents of the local veterans home. And if new buildings are required, VA should consider putting them in Hot Springs instead of another community such as Rapid City.

Anything less will devastate the region, Renstrom and other veterans say.

“I’m 65,” he says. “I own a home here. If they pull out, I’ve got nothing. Me and thousands of other veterans.”

Ken Olsen is a frequent contributor for The American Legion Magazine.

- Magazine