Commander of 1963 Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon will never forget his days guarding the president’s casket.

“Where were you when you heard about JFK?”

William F. Lee, now a retired Marine major, clearly remembers where he was on Nov. 22, 1963, 50 years ago this month. He was playing in an intramural football game when a courier delivered news that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. For Lee, it was a call to action. He was the commander for the Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon at the Marine Barracks in Washington.

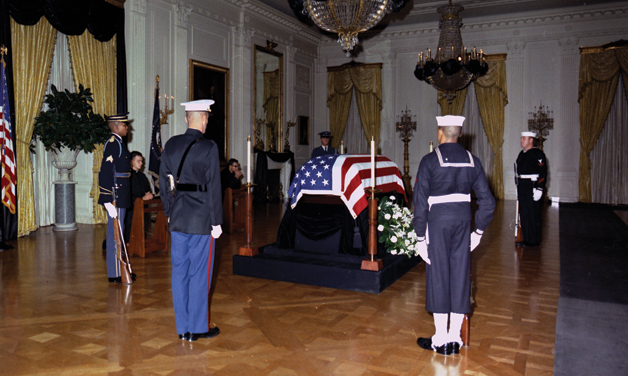

In the days following the assassination, Lt. Lee and his men served on what they call “death watch,” standing guard at the president’s casket in the East Room of the White House and at the Capitol Rotunda. “It was completely silent in there. And one was left alone with his thoughts, which made it very difficult,” says Lee, one of three Marines to receive the Army Commendation Medal for his service during that time.

A group of five – one servicemember representing each branch of the military – would stand guard for 30 minutes, then rotate out for another group and take a break for two hours.

“It didn’t seem like two hours,” Lee recalls. “Thirty minutes was gone just getting off and on again. When we came off watch, we took off our uniforms. And in the case of the Marines, we pressed them and shined the brass, and spit-shined the shoes. Then had a cup of coffee, and by the time you did all that, it was time to put your uniform back on again and get ready to go, then get inspected by the officer, and then go back up and start the procedure all over again.”

That’s how it went for several days, except for one impromptu private Mass for the Kennedy family. About 25 minutes into one of Lee’s watches, the officer in charge whispered to him that there would be a Mass, and Lee’s group would stay on for the duration.

Lee says all the Kennedy family members were there, along with some Cabinet and staff members – 30 to 50 people in all.

“We were still at attention, and the Mass went on another 50 or so minutes,” Lee says. “It was excruciating to stand there at attention that long, not blinking, being perfectly motionless like a mannequin. The family – Jackie, John-John and Caroline – were sitting directly in my line of vision at the foot of the casket, along with Robert Kennedy, Ethel Kennedy, and Ted Kennedy and his first wife. So that was disconcerting. I just had to do math problems in my head.”

After the Mass, each Kennedy family member stopped and prayed at the casket, Lee says. Then Jackie and the children paused at the head of the casket. “She said some prayers. I couldn’t hear the words. That was a little tough to handle.”

Lee says someone accompanied the two children out while Jackie stayed and “put something in the casket. I don’t know what it was, and then she got up and left. Beyond her, I could see the relief watch had formed in the hallway, so I knew we were going to get off watch finally after about an hour and a half of staying at attention. She (Jackie) turned back and looked at the casket. It was the most forlorn look that I have ever seen. I mean, it was just stunning. It was like someone stuck a knife in me. I was thankful that the watch came on and relieved us in a few minutes because I was more than ready to leave.”

Later, the “death watch” squads served at the public viewing in the Rotunda. Lee says that while the routine was largely the same – 30 minutes on, two hours off – the setting, the crowds and the TV cameras provided a stark contrast to the serene duty in the East Room.

“The TV cameras were filming or doing something almost all of the time,” Lee says. “It was like having 200 degrees on the back of your head and neck, and your back. And out front, the doors were open. It was November and there was a coolish breeze. I guess it was in the 30s. So you had some cool air on your forehead, and the difference between the two was disconcerting.”

The squads remained as still as mannequins amid other distractions. “Every other person in the crowd had a flashbulb camera. And when they got to the front of the casket, there were flashbulbs going off all the time.”

While standing in silence, Lee reflected on what he calls his “personal eyeball contact” with President Kennedy a few months before his death. Lee had often served during special presidential events, including the arrival of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” in the United States for a tour earlier that year. After a dinner reception at the National Gallery of Art, the president and his wife were supposed to take an elevator up one floor to meet their guests. But the elevator wasn’t working correctly, and when the first couple stepped out of it, they were right alongside Lee, who was standing at attention. As they waited for the elevator to be repaired, he listened to their conversation – one he’ll never forget.

“Jackie said, ‘Jack, let’s just go up the steps,’” Lee recalls. “He said, ‘No, no, no. Let’s wait for the elevator.’ This conversation was repeated several times. Finally she said, ‘Jack, let’s go up the steps. Everybody is waiting.’ He said, ‘OK,’ and as he turned to me, he said, ‘Don’t worry. I make all the big decisions.’ Of course, I was a mannequin, so I didn’t laugh.”

Henry Howard is deputy director of magazine operations for The American Legion.

- Magazine