American Legion war correspondent had up-close access to the official end of World War II.

American Legion Magazine Managing Editor Boyd B. Stutler had temporarily shed his title and primary job to report firsthand the final chapters of World War II. His byline changed to Boyd B. Stutler, “war correspondent.”

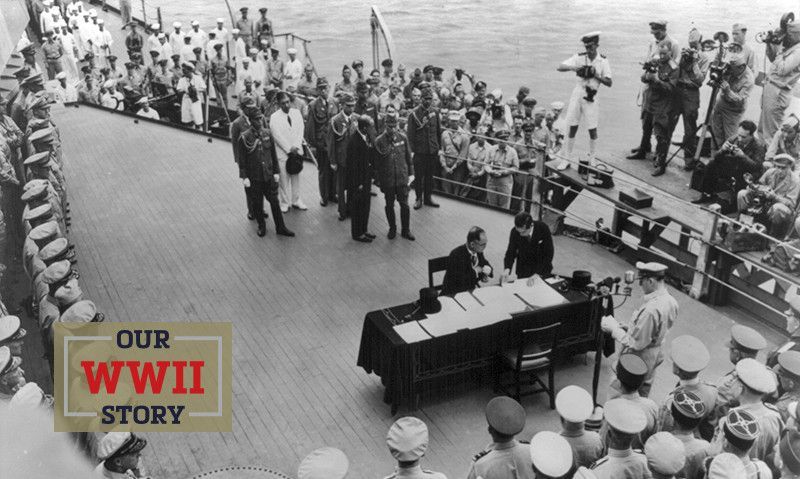

And on Sunday, Sept. 2, 1945, that role placed him on the deck of history. His report in the November 1945 issue of the magazine described the final moment of World War II – the Japanese surrender onboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

“From a favored position on a turret overlooking the veranda deck, I watched while the stage was set for the ceremony,” Stutler wrote. “I saw the delegations of Allied signatories and the array of military and naval leaders who had led the victory come up the ladder from their launches, past a Marine guard of honor on the quarterdeck, to their assigned places on the veranda while the ship’s band played national anthems and patriotic airs.”

Flags of the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and China fluttered in the breeze above the 58,000-ton battleship.

“Last of all to cross the quarterdeck and take their place in the open center of the veranda was the 11-man Japanese delegation led by the lame Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, flanked by Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu, chief of staff of the Imperial Army. Their arrival on the exact scheduled minute was the signal for opening remarks by Gen. (Douglas) MacArthur.”

The ceremony, Stutler reported, “was most impressive in its simplicity.” One table. Two copies of the instrument of surrender. Two chairs. Also displayed was “a case enclosing the first American flag ever to fly over the soil of Japan – the one raised by Commodore Matthew C. Perry on the occasion of his historic visit on July 14, 1853. Overhead, flying in the soft morning breeze as the ship’s colors, streamed the flag that flew over the Capitol at Washington on Dec. 7, 1941, which later flew over Rome and at the Potsdam Conference, from which emerged the terms of this day’s unconditional surrender.”

Gen. MacArthur – dressed “for the field in suntan uniform … wearing his battered old cap made familiar to nearly every American at home” – prepared to speak. Behind him were Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz; Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, hero of Corregidor; Lt. Gen. A. E. Percival, commander of British forces at Singapore; “and a dozen other generals and admirals who had contributed mightily to the defeat of Japan. What a setting for a painting – MacArthur and his generals, Nimitz and his admirals.”

“We are gathered here to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored,” MacArthur began. “It is my earnest hope and indeed the hope of all mankind that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the carnage of the past – a world founded upon faith and understanding – a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance and justice.”

Foreign Minister Shigemitsu limped to the table, signed the instrument and “walked stiffly back to his place,” Stutler wrote. “He was followed by Gen. Umezu, who bent over the table to sign after a brief scrutiny. These two were the designated signatories. Stiffly erect, with stony faces, they watched the delegates of the Allied nations file past to sign the documents.”

Stutler noted that Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, two years dead at the time of the surrender, had boasted that he himself would dictate terms of peace at the White House in Washington, D.C. Other Japanese military leaders, Stutler added, “had committed hari-kari to ‘atone’ for the national military defeat.”

Representatives of the Allied nations rapidly signed the instrument as U.S. planes were on alert nearby in case any treachery might be in the plans, with so many high-ranking Allied leaders in one place.

“Adm. Chester W. Nimitz signed for the United States of America, Gen. Shu Yung Chang for China, Adm. Sir Bruce Fraser for the United Kingdom, Lt. Gen. Kuzma Nikolaevech Derevyanko for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Gen. Sir Thomas Blarney for Australia, Col. Moore Cosgrave for Canada, Gen. (Jacques Philippe) Leclerc for France, Adm. C.E.L. Halfrich for the Netherlands and Air Vice Marshal Len Issitt for New Zealand.”

The entire ceremony took 20 minutes. At 9:20 a.m., MacArthur succinctly and definitively punctuated the war that had claimed some 70 million lives worldwide: “Let us pray that peace be now restored to the world and that God will preserve it always. These proceedings are closed.”

Stutler wrote that when he landed at Atsugi airstrip on Aug. 30 and made his way into Yokohama in advance of the surrender ceremony, the Japanese were subdued, curious and even “excessively polite. All along the route, the citizens peered out from behind the shutters of their homes, or stood gazing by the roadside. Military guards turned their backs and faced outward as the convoy approached, but the interpreter explained that this was not done in discourtesy or contempt but to safeguard against any attack from the rear.

“In Yokohama, there were but few people on the streets, and the American troops created no more stir than a picnic party passing through an American village. Yokohama suffered much damage, principally in the industrial areas.”

Stutler continued to reference to the destruction at Manila and Pearl Harbor as he viewed the devastation in Yokohama, noting that the Japanese were “smiling, seemingly anxious to please … intent on ingratiating themselves in the good graces of the troops and of the high command. But their attitude of sincerity does not carry complete conviction. To those of us who view the scene critically, it is difficult to recognize the present attitude of these gentle people with the bestial brutality and studied sadism of the Japanese soldier in the field. Surely such a miracle as the regeneration of an entire race could not come to pass overnight. But there is still hope. At best, the fangs of the Black Dragon have been drawn and his claws clipped – the more hopeful believe that he has been wounded unto death and with his passing, the spirit of militarism and lust for conquest will die. Perhaps a new Japan will rise from the ashes to dignify her place among the nations of the earth.”

- Honor & Remembrance