During World War II, radio brought troops worldwide home, if only for a night.

The night before Christmas, a time when so many talk and sing about peace on earth and goodwill among men. That particular year, though, there was precious little peace or goodwill to be found.

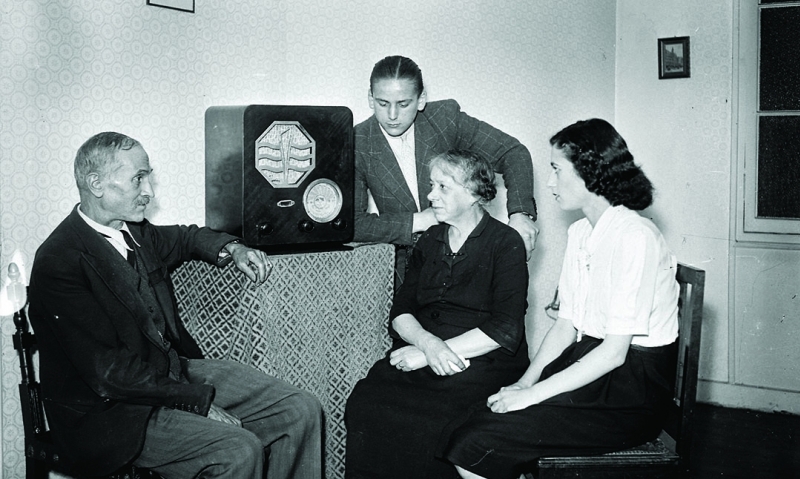

Early church services were completed for many. Midnight Mass had not yet begun for others. Across America, families, neighbors and friends gathered in parlors and living rooms to share food and conjure up as much holiday fellowship as they could manage. Many of them were purposefully sitting before their radios, the dial lamps offering a bit of cheer, awaiting the start of a show scheduled to begin at the top of the hour. Cabbies, on a typically slow night, parked nose to tail along curbs, engines idling to keep warm and at the ready for the occasional fare, their dashboard radio receivers switched on. In barracks at induction centers and military facilities around the country, men awaiting training or completing preparations to ship out to battlefields around the world gathered near any available radio speakers, ready to listen to what promised to be a very special broadcast. One that featured some of their own brothers in arms already over there, at or near the front.

It was one of those rare media events, usually reserved for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “fireside chats” or other such major addresses by world leaders during an especially troubled time. But on that one winter night, all four major radio networks in the United States – CBS, NBC Red, NBC Blue and Mutual – turned over their airwaves to a single program, one mostly made up of singing and joke telling. And that included several amateur singers and musicians, and some truly lame jokes and sketches.

At 10 p.m. in New York, the announcer on the NBC networks apologized because their regular shows would not be broadcast that night, pre-empted by this special holiday presentation. Those included “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” “Bill Stern’s Sports Newsreel” and “Fred Waring in Pleasure Time.”

But so far as we know, few listeners complained, not about the missed regular programs or the lame jokes.

It was a Friday evening, Christmas Eve 1943, two trying years into World War II. That radio broadcast, “Christmas Eve at the Front,” was designed to give audiences in the USA a real-time glimpse of soldiers and sailors, arrayed around the planet during that holiday season, fighting brutal enemies on many fronts. And to allow those servicemembers the opportunity to speak to the folks back home via the newest and fastest-growing mass medium of the day.

At that time, more than 90 percent of Americans had access to a broadcast radio. News and entertainment programming on the air was, for the first time, rivaling newspapers as the medium of choice for news and entertainment. Even those who could not afford to subscribe to a paper could usually find a radio to listen to. Important programming attracted huge audiences. Many of FDR’s “fireside chats” reached more than 70 percent of the country’s population – Super Bowl-like numbers! Stephen Early, FDR’s press secretary, had had little trouble convincing his boss of the power of the medium when he delivered his first calming nationwide address into a microphone back in 1933, while the nation was still in the throes of the Great Depression.

“It cannot misrepresent or misquote. It is far-reaching and simultaneous in releasing messages given it for transmission to the nation or for international consumption,” Early maintained.

On that Christmas Eve, a live audience gathered in a radio studio in Hollywood, ready for the broadcast to begin promptly at 7 p.m. local time. The show was scheduled specifically so it would air in what was already being called “prime time” across all four U.S. time zones. Those present in the audience that night, coached to applaud and laugh when prompted by flickering or lighted signs, or those who dialed into the program on radios across America, had no idea of the months of work and planning done by technicians around the globe to make this show possible.

Those engineers were about to attempt something thought impossible only a few years before. They were going to bring live voices from widely-arrayed spots on Earth to a single point so their songs, jokes, skits and greetings could be rebroadcast to eager listeners sitting before their radio receivers back home. The first trans-Atlantic telephone cable capable of carrying voices was still a decade away. Communications satellites were the stuff of science fiction. This big show would have to rely on relatively new technology and the vagaries of shortwave signal propagation if it was to happen.

It was an all-star production, and likely would have commanded high listenership even without its technical and heart-tugging aspects. The idea had actually been concocted by the military, that believed such a real-time broadcast would be a tremendous morale boost not only for the fighting forces and those supporting them, but also for their families back home, separated during this holiday season by an awful globe-spanning war. Its participants reminded listeners several times that the idea for the show came from the forces themselves, not from the networks.

When it came time to select the program’s primary host, the choice was obvious to everyone, and the person chosen was enthusiastic about the opportunity.

At the time, Bob Hope’s network radio show, sponsored by Pepsodent toothpaste, commanded huge audiences each week. He had started his showbiz career on the vaudeville stage, and by 1934 was already working in radio and the movies. Ironically, his first major Hollywood film was “The Big Broadcast of 1938.” It was also in that feature that he introduced the song “Thanks for the Memory,” which would become his trademark theme. That tune would also have special meaning when Hope used it to close his hundreds of United Service Organizations (USO) appearances, starting in May 1941 and, with a total of 57 tours during multiple conflicts, lasting all the way to 1991.

However, once the show begins, the first voice the radio audience hears is not Hope’s. After a rousing orchestra rendition of “Jingle Bells,” an announcer introduces distinguished actor Lionel Barrymore. Apparently, Barrymore’s portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge in the annual radio production “A Christmas Carol” made it appropriate that he be a part of “Christmas Eve at the Front.”

Even so, his deep, sad voice sounds almost out of place after the peppy musical introduction as he begins, “Well, it’s Lionel Barrymore here in Hollywood, and here it’s Christmas Eve, the third our country’s experienced in the war. But tonight, I’m not going to play the part of Scrooge.”

Instead, Barrymore promises to take listeners “by the hand to the side of your loved ones fighting at every quarter of the globe.” No small task in those days, but that is exactly what this extraordinary production attempts to do for the next 70 minutes. Barrymore maintains that those tuned in will visit Italy, North Africa, New Guinea, Guadalcanal, New Caledonia, China (“where it’s already Christmas”), India, Panama, Alaska, Pearl Harbor and even “some of the ships of our Navy.”

Then the actor introduces Hope, “whose name is synonymous with joy to the GI.” “The guest conductor of this worldwide tour,” as Barrymore describes him, immediately picks up the pace and the show is on. When greeted with loud applause, Hope quips, “Thanks, relatives!” As usual, the comic’s jokes are topical. “It has been so cold in the Midwest that even the Republicans are waiting for the ‘fireside chats.’” Then, after a few zingers, the truly challenging part of the production begins.

The first stop on this electromagnetic journey is North Africa and Algiers. The hum and static of the shortwaves is obvious and the signal fades a bit at times, but an unidentified voice tells us it is just after 3 a.m. as he reads from a prepared script. He informs listeners that despite the holiday, this will for the most part be a typical day for the men working there. A soldier from Sheffield, Ala., comes on mic and, with a deep Southern accent, talks about how he and his fellow troops spent Christmas Eve so far from home.

It is difficult for us today, accustomed as we are to instantaneous, high-definition, live communications from anywhere on the planet, to imagine how impressive this short, wavering presentation was to the audience – those in the studio in Hollywood as well as the millions sitting before their radios in living rooms around the country.

Indeed, most of them had recently heard reporter Edward R. Murrow as he dramatically described the Nazi bombing of London live, as it happened. He had been able to do those riveting reports by employing a shortwave transmitter, just as this Christmas special was attempting to do. But the voice the audience was hearing this night was that of a soldier, a regular guy, and it is Christmas Eve as this first distant transmission wraps up with, “We return you to America.”

There may well have been some wishful thinking in those five simple words.

Bing Crosby, Hope’s usual foil and movie partner, joins the broadcast then, along with the Army Air Force Orchestra, with a very quick verse and chorus of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.”

Some of the segments that night came through so clearly that, based on their technical quality, they were almost certainly prerecorded, most likely using either wire or metal tape-recording technology then available. That was especially true of the reports from an aircraft carrier and a battleship, the latter from which a sailor sings a beautiful tenor version of “Gesu Bambino.” Of course, the names and locations of those ships were never given on the air, nor were those segments ever portrayed as anything but live and in the moment.

Except for atmospheric noise and some fading, most of the remote shortwave transmissions were surprisingly listenable. Others were difficult to understand, but that was to be expected. Some transmission paths attempted during the program did not work at all.

At one point, when there was nothing coming through from Alaska, someone off-mic can be heard saying, “No copy,” meaning that if there is a signal it is not readable. Another time, the listening audience can hear someone saying, “Go ahead, Panama,” since those standing by at most of the far-flung spots could not actually hear the broadcast to which those back home were tuned. They had to be prompted over the shortwave radio circuit to begin their presentations.

Knowledge of shortwave propagation was quite limited in those days. That portion of the radio spectrum was still an unfamiliar quantity, mostly occupied by “ham” radio operators. Such long-distance radio transmissions were subject to not only seasonal variations but could even fluctuate day to day or hour to hour. Northern latitudes are especially problematic. Such glitches were likely an anticipated possibility for the broadcast. Hope, Crosby and the rest of the crew handled the situation smoothly, ad-libbing, throwing in their typical jibes at each other until they could verify there would be no bit from that “quarter of the globe.” Each time a signal from some distant part of the world was not able to make the trip, they moved on to the next segment. The planned 90-minute broadcast ended 15 minutes early because of the missed segments.

About 45 minutes into the program, a message from FDR, recorded earlier in the day, is broadcast. In his typically calm, strong and positive voice – though stopping a few times to cough and clear his throat – he reports on recent talks with other world leaders, discussing not only the continued progress in the war but what will happen when the fighting is concluded. He also takes this opportunity to announce that the new supreme commander of America’s war effort in Europe will be Gen. Dwight Eisenhower. Speaking for about half an hour, the president in effect delivers yet another inspirational “fireside chat.” It is clear from this segment that he does indeed understand the power of this still relatively new medium, and how the right words and intonation can positively affect the mood of the country.

Despite FDR’s optimistic outlook and strong voice, he would die only 14 months later, and World War II would rage on for almost two more years.

The Army Air Force Orchestra concludes “Christmas Eve at the Front” by playing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” And the NBC announcer once again apologizes for the network’s having pre-empted “Amos ‘n’ Andy.”

It is difficult for us today to imagine what effect this broadcast might have had on its listenership across the country. We know there was a large audience tuned in, though there appears to be no ratings information available. We also know it was one of the first times in which participants from so many points of the globe were able to speak live on a radio broadcast, letting their fellow Americans hear – in real time – what life was like where they were and how they were spending the holiday.

Even so, despite so much of the show being obviously scripted and with the expected technical hitches, this historic broadcast almost certainly accomplished its goal. Families had to feel better knowing what their friends and kin – more than 3.5 million were deployed overseas at the time of the show – were experiencing at the front. And thanks to this exciting, relatively new medium and the hard work of so many who made it possible, they certainly felt just a bit closer to those loved ones so far from home on that special night of the year.

As noted, Hope was not finished with his efforts to make wars a bit more tolerable for those who were bravely fighting them. He entertained the troops, at home and in war zones, for more than 60 years, performing in more than 200 USO shows for men and women in uniform. Hope lived to 100, and in October 1997 U.S. House Joint Resolution 75 was signed into law giving him honorary veteran status for his humanitarian work with the military.

Thanks to another media innovation, “Christmas Eve at the Front” can still be heard today in its entirety – blemishes and all – at several websites, including on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=BT3DyAu9Rqc and the Old Time Radio Downloads site at www.oldtimeradiodownloads.com/wwii/christmas-eve-at-the-front/guest-bob-....

Listen, and maybe you too can get a feeling for how this 75 minutes of radio, “conceived by the boys who are far from home this Christmas season,” brought just a bit of holiday joy to those who so desperately needed it.

Don Keith is a best-selling author and award-winning broadcast journalist. He writes both fiction and nonfiction, including extensively about World War II history. His website is www.donkeith.com.

- Honor & Remembrance